Afghan Tourism Brain Drain

“It was demolished years ago” our Herati guide asserts confidently. We’ve asked to be taken to one of the city’s ancient caravanserais, and have several recent pictures of the in-tact site on our phone. We’re fairly confident the site still exists and eventually our guide admits that it’s his first day on the job. The truth is that he’s no idea where any of the sites in the city are – he was recommended to us because he spoke some English.

Herat was one of the few cities in Afghanistan that enjoyed a (very) slow trickle of foreign tourists over the last 20 years. These foreign visitors along with NGO’s involved in protecting the country’s cultural heritage (notably the Aga Khan Foundation), meant that Herat had a small but informed group of experts and guides ready to explain and explore the city with.

Unfortunately many of those who had connections with foreign NGO’s or had been involved in foreign projects before the return of the Taliban used those connections to flee. This has left painfully few people who even know where some of the country’s most famous sites are, never mind any information on their history.

One of our key goals in our Afghanistan project is to put money directly into the pockets of regular Afghans, who through no fault of their own have found themselves at the sharp end of international sanctions. Unemployment is extremely high and we are always besieged with offers of people who want to work or help us. Guiding and helping us on our tours is a great way for local people to earn some extra cash, and also spend time chatting with foreign tourists about the outside world – but we can’t just pay anyone who is recommended to us as a passenger.

We also can’t employ anyone who makes our lives harder or more complicated – we’ve spent many hours driving round in circles with so called guides, spending time asking directions, seeking sites in the wrong neighbourhood or being told that our grid locations are sure to be inaccurate.

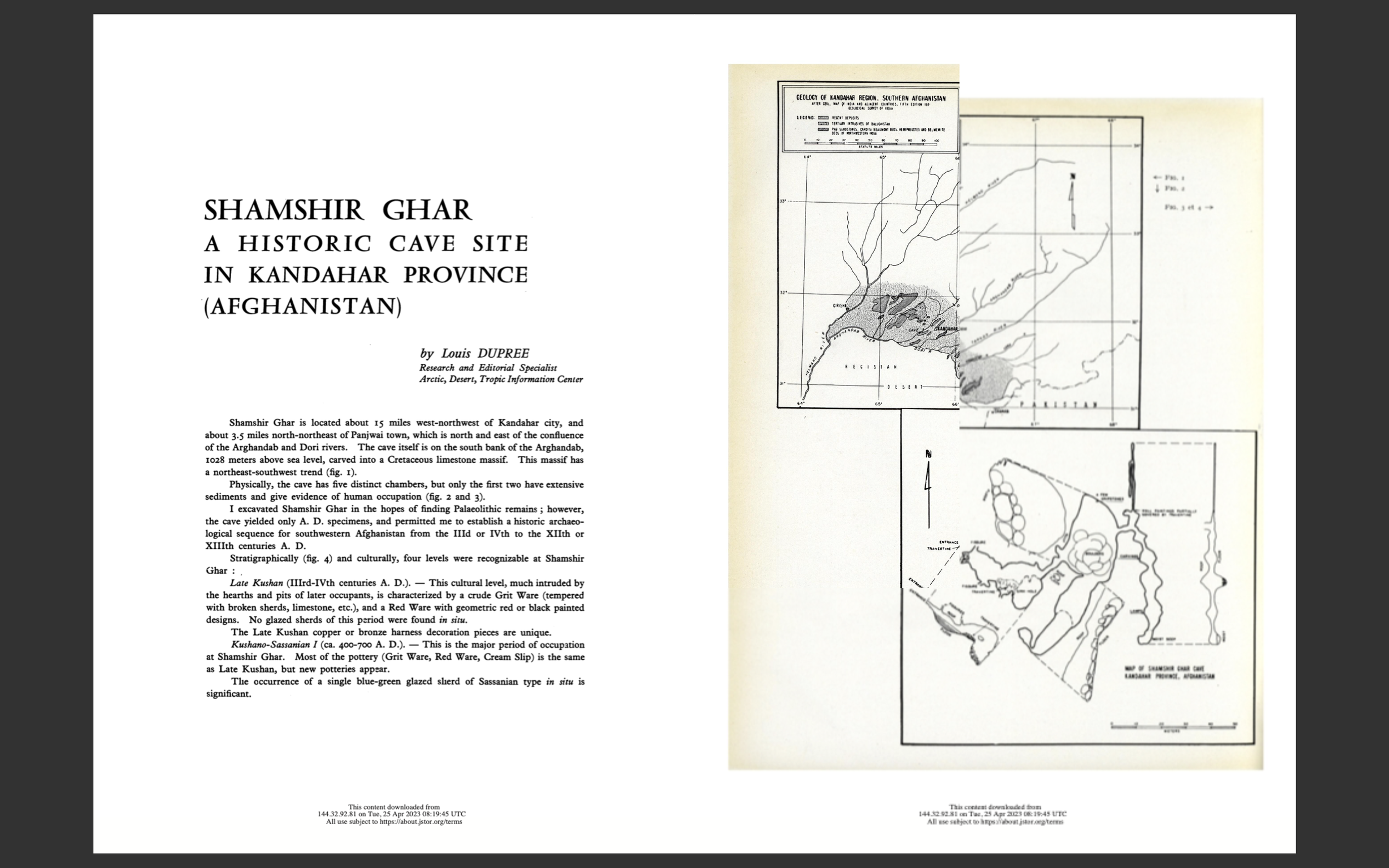

At the moment, we sometimes feel that we’re better off alone without local help because of the amount of time we waste with our “guides” – sometimes archaeological papers from as far back as the 1950’s have been useful to us in understanding unexplored and remote historic places. But this isn’t what we came to Afghanistan to do – from the very beginning we wanted our tours to be about Afghans telling their own stories, in their own words and defiantly not in the words of European colonialists!

The problem is not unique to Herat. In Bamiyan we have been recommended trekking guides who have never been to the mountains. In Lashkar Gar we spent several hours arguing with our appointed guide about the existence of Lashkari Bazar. The site is an incredible ruin of the palatial residence of the rulers of the Ghaznavid Empire – it should be one of Afghanistan’s premier attractions.

When we eventually followed a GPS point to the palace’s location, the local guide was shocked. He couldn’t believe that despite living in Helmand his entire life, that he’d never visited the place.

In some ways the lack of any tourist infrastructure is what makes visiting Afghanistan charming. Our trips still feel like we are trailblazing and discovering sites that nobody has been able to visit for more than 40 years – but there is a happy medium which we haven’t quite reached yet. Over the next few months we hope to be able to invest in a small network of local guides, to encourage them to proudly become experts their own areas and history.